BY BETSY STOVSKY, RN, MSN, AND MARY McLAUGHLIN DAVIS, DNP, NEA-BC, ACNS-BC, CCM

Patients with infective endocarditis (IE) due to opioid substance use disorder (SUD) and injection drug use (IDU) present to the acute care setting with a myriad of surgical, medical, psychiatric and social problems. The complexity of this patient population requires an experienced team of healthcare professionals to provide the care they need from admission to discharge. Case managers, as leaders in population health, patient advocacy and continuity of care, are important members of the multidisciplinary team to care for this patient population.

The numbers are alarming and increasing. The rate of overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids was more than 18 times higher in 2020 than in 2013 (CDC, 2023). Ohio experienced 4,110 deaths in 2020, a 31.8% change from 2019 at 3,117 deaths.

In 2020, Ohio experienced a rate of 331 per 100,000 opioid-related hospitalizations. The national rate is 250 (ahrq.gov). Bacterial infections are the leading cause of SUD hospitalizations and deaths in hospitals. The infections are commonly skin, soft tissue, joint, abscesses, phlebitis and infective endocarditis. IE is a life-threatening bacterial infection, causing inflammation of the heart valves and chambers (Cleveland Clinic, 2020).

Cleveland Clinic Heart Vascular & Thoracic Institute (HVTI), with 422 inpatient beds and 13,165 patient admissions, is a national referral center for endocarditis, as well as a center for patients with IE and opioid use disorder (OUD). As the nation saw an increase in opioid use and related hospitalizations over the past 10 years, the HVTI experienced a 23% increase in patients admitted for IE and OUD requiring surgery. Patients having surgery at Cleveland Clinic for IE do better than expected despite the high acuity and complexity of their surgeries, and like other reported outcomes, those who survive surgery and hospitalization do well for the first 90 days (about 3 months), but then the risk of poor outcomes increases. This highest risk period appears to be between postoperative days 90 and 180, when patients who inject drugs have an approximately 10-fold higher hazard of death or reoperation compared with patients who do not inject drugs. Reoperation over time is also higher for those who inject drugs, often necessary due to recurrence of OUD-IE. (Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 2015). Five-year rate of death for those surgically treated remains higher for those with IDU related to relapse, recurrence of IE, age and congestive heart failure (Caceres, Malik, Naeem, et al., 2022).

Patients with SUD-related IE tend to have high acuity, co-morbidities and require long hospital stays. In 2012, the estimated total charge per hospitalization related to OUD was $28,543, and infection due to OUD was $107,217. The most common payer in 2012 for both groups was Medicaid. Comparing both groups in 2012, the patients with OUD and infection were more likely to be uninsured (Ronan, Herzig, 2016). This has become a financial burden for hospitals across the country.

Medicaid primarily covers the OUD population at Cleveland Clinic. However, as beneficiaries are required to re-enroll in Medicaid because the emergency pandemic provisions are no longer in place, this may convert to loss of overage. As a national referral center, Cleveland Clinic often treats patients from surrounding states. Patients with out-of-state Medicaid are not eligible for a skilled nursing facility providing post- acute intravenous antibiotics in Ohio, and hospital case managers often cannot find a suitable facility in the patients’ home state. In addition, skilled nursing facilities often have concerns with patients who are receiving IV antibiotics and have an untreated SUD. The security risk it can pose is too much for many already understaffed SNFs to handle. This causes a long length of hospital stay that is costly and unnecessary. It also creates barriers in throughput for all patients requiring cardiac surgeries.

The rise in the use of opioid-related surgical hospitalization in the past decade raised alarm bells for Cleveland Clinic multidisciplinary teams, particularly HVTI. The cardiovascular and thoracic surgeons recognized the futility of providing surgical intervention for this special population without treating OUD, the underlying cause of the endocarditis. HVTI’s leader in this initiative, Dr. Gosta Pettersson, retired vice chairman of Cleveland Clinic HVTI stated, “We would not operate without antimicrobials, so why would we operate if the addiction is not treated and associated with such high risk of relapse and death?”

The creation of the Management of Substance Use Disorder Heart Infections in Cardiovascular Patients at Cleveland Clinic (MOSAIC) Program was developed to address both diagnoses, SUD and endocarditis. The multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, social workers, therapists and case managers acknowledged the urgency and necessity of providing a holistic program for patients. The program was developed through a collaboration of a) advanced practice providers, b) behavioral health, c) cardiothoracic anesthesia, d) cardiovascular medicine, e) cardiovascular surgery, f) Center for Connected Care, g) care management, h) infectious disease, i) information technology, j) nursing, k) peer support — Supporting Opiate Addiction Recovery (SOAR), l) social work and m) art/music therapies.

MOSIAC has four objectives.

Early identification of patients with care coordination from admission to discharge and post discharge, utilizing the electronic medical record.

Standardized protocols for pre-op, peri-op and post-op care with timely consults to appropriate services, such as Behavioral Health for Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT); therapies such as exercise physiology, physical, occupational, art and music; peer support (Project SOAR, an outside resource); and case management/social work to initiate early care coordination, discharge planning and transition of care to appropriate post discharge facilities.

Care management and nursing support and resources throughout hospitalization and post discharge through regular follow-up phone calls and continuity of care.

Track outcomes, program evaluation and program changes based on data.

From December 2019 through April 2022, 171 patients participated in the MOSIAC Program, 76% stated they use some type of opioid and 70% admitted to intravenous (IV) drug use.

Recognizing the benefit of medication-assisted therapy in preventing relapse, all patients are assessed by behavioral health. Eighty percent were discharged on MAT. Of those not on MAT, only four declined. Others were not discharged on MAT for various reasons including sober at time of admission.

An important part of the program has been peer support. Peer supporters visit patients a few times a week to offer support. Of the 171 patients, 56% had SOAR; this number has increased post COVID restrictions.

MOSIAC patients receive a binder outlining the MOSAIC process. It provides education regarding endocarditis and how it is related to OUD and includes the necessary patient recommendations, precautions, medications, activities and resources related to patient recovery for endocarditis, valve disease and SUD. There are provisions for the patient to personalize the binder with pages for notes, reflection and even intricate patterns for coloring, complete with a set of colored pencils.

Case management is integral to the MOSAIC process. The challenge for hospital case managers for this patient population is formidable. The determinants of health factor into every aspect of short- and long-term care planning. The patients are medically and surgically complex with life threatening endocarditis requiring intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy and probable cardiothoracic surgery. In addition, the root cause and main problem, substance use disorder, is a life-threatening disease requiring treatment. Many patients in this population also have a mental health diagnosis, so they need an integrated case management plan to address all three major problems. Compounding these issues are lack of social support, housing, finances (including insurance), transportation and education.

The Case Management Standards of Practice place the patient at the center of all case managers’ planning (CMSA, 2022), and hospital case managers realize MOSIAC patients need guidance, support and empathy throughout the hospitalization. The CMSA Integrated Case Management (ICM) model promotes relationship-based care achieved through conversational assessments and motivational interviewing. Using the ICM lens, the hospital case manager assesses the patient’s current and future socioeconomic risks, in conjunction with the medical, cognitive and behavioral hazards. ICM seeks to mitigate setbacks, motivate patients to care for themselves and prevent future catastrophic events (Fraser, Perez, Latour, 2018).

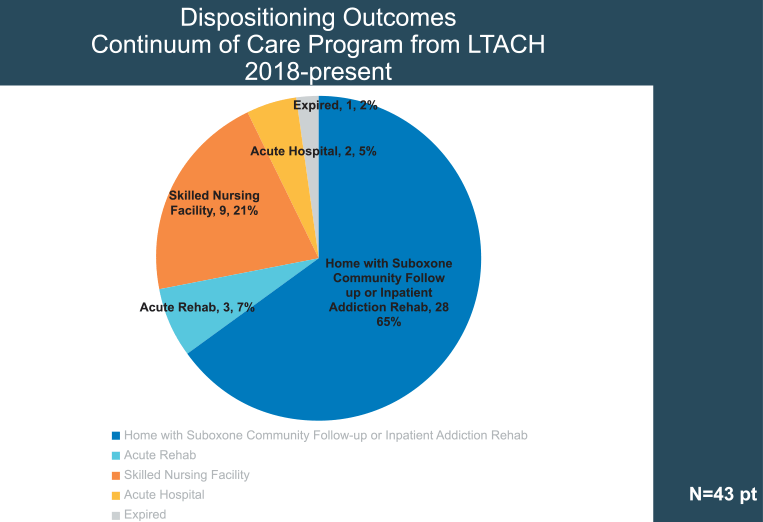

Figure 1. Source: CLEVELAND CLINIC AND SELECT MEDICAL/CLEVELAND CLINIC

The challenge of case management and success of MOSAIC relies on transition of care. The establishment of a protocol in collaboration with a partner long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) early in the program addressed the three major problems patients face. Patients continue to 1) receive community outpatient antibiotic therapy through a hospitalist and infectious disease specialist; 2) receive continuation of MAT, commonly Suboxone with counseling every week on site provided by Cleveland Clinic psychiatry group; and 3) ongoing community-based addiction programs on discharge, arranged by the social workers and case managers. (Figure 1.) Through the LTACH continuum of care program, 65% of patients discharged home with Suboxone, community follow up or inpatient addiction rehabilitation, 7% discharged to physical acute rehabilitation, 21% to a skilled nursing facility, 5% returned to acute care and 2% expired. The barrier to using this program for all MOSIAC patients is they do not all qualify for LTACH. From 2018 to the present, only 43 patients with IE and SUD moved to LTACH.

There exists a strong need for a facility that allows IE-OUD patients to discharge from acute care and transition to ongoing addiction and psychiatric care with skilled nurses to monitor cardiac status, administer intravenous antibiotics and ideally an intensive outpatient program (IOP) to treat their SUD, with transition of care to appropriate resources at time of discharge (such as sober housing with a MAT Clinic, or inpatient recovery if needed). Many patients may have undergone heart surgery and therefore have postoperative care needs, while others may be awaiting cardiac surgery while they demonstrate a commitment to ongoing addiction therapy in preparation for cardiothoracic surgery. Cleveland Clinic is collaborating with a residential substance use disorder facility that has experience treating OUD; however, an intense training program is necessary to educate the nursing and ancillary teams on how to manage a central line, infuse antibiotics and care for post-op cardiac patients.

In the interim, our case managers are strengthening the relationships with the skilled nursing facilities (SNF) that provide MAT and intensive outpatient therapy. Many patients are lost to follow up once they discharge from acute care to a SNF. Hospital case managers now recognize the need to provide verbal reports to the SNF director of nursing and for the same director to call the case manager when the patient discharges from the SNF, no matter the circumstances. Ideally, they will contact the case manager if the patient declines participation in the IOP or refuses MAT. The MOSIAC team may have an opportunity to intervene and discuss the high stakes of relapse with the patient and the high risk of death due to reoccurring endocarditis.

The MOSAIC program’s success depends on team members committed to caring for patients with SUD-related IE. Case managers are a necessary and key component in this challenging population as they assess the patient and assist them through their hospital stay and transition of care post discharge. Knowledge of the ICM Model, care needs of the IE-SUD population and resources available is essential.

REFERENCES

https://cmsa.org/sop22/.

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/116957-endocarditis.

https://www.ahrq.gov/opioids/map/index.html.

https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/synthetic/index.html.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/dhcs/drug-use/drug-use.html.

Caceres J, Malik A, Ren T, Naeem A, Clemence J, Makkinejad A, Wu X, Yang B. Poor long-term outcomes of intravenous drug users with infectious endocarditis. JTCVS Open. 2022 May 31;11:92-104. doi: 10.1016/j.xjon.2022.05.013. PMID: 36172440; PMCID: PMC9510881.

Fraser, Kathleen, B. S. N. Rebecca Perez, and Corine Latour. CMSA’s integrated case management: A manual for case managers by case managers. Springer Publishing Company, 2018.

Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations Related To Opioid Abuse/Dependence And Associated Serious Infections Increased Sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016 May 1;35(5):832-7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424. PMID: 27140989; PMCID: PMC5240777.

Shrestha NK, Jue J, Hussain ST, Jerry JM, Pettersson GB, Menon V, Navia JL, Nowacki AS, Gordon SM. Injection Drug Use and Outcomes After Surgical Intervention for Infective Endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015 Sep;100(3):875-82. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.019. Epub 2015 Jun 19. PMID: 26095108.

Betsy Stovsky, RN, MSN, is currently a consultant, retired as manager, Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute Patient Resources and Outreach, working as project manager on various projects at Cleveland Clinic.

Mary McLaughlin Davis, DNP, NEA-BC, ACNS-BC, CCM, is a Certified Case Manager, clinical nurse specialist and was senior director for case management Cleveland Clinic Main Campus and Akron General Hospital until her retirement in 2022. She is currently a project manager for case management Cleveland Clinic. She served as an executive board member of The Case Management Society of America, from 2013 to 2019 and president from 2016 to 2018.

Image credit: ISTOCK.COM/NADZEYA HAROSHKA

The post Case Management Leads the Team in Transitions with Patients with Substance Abuse Disorder and Infective Endocarditis appeared first on Case Management Society of America.

Source: New feed