BY KELVA EDMUNDS-WALLER, DNP, RN, CCM, WITH NICOLE M. MEREDITH, BSN, RN, CNOR, CSSM

The United States of America, one of the world’s wealthiest and most technologically advanced countries, has a Black and Brown maternal and infant health crisis. Healthcare costs in the U.S. are twice the expenditures of other wealthy countries. Despite its wealth and state-of-the-art healthcare, women and babies of all races in the U.S. die at rates higher than in most other industrialized countries. For over a century, the deaths of birthing women and infants of color have far exceeded those of White women and infants. Grassroots activists, including non-profits and community-based organizations across the country, are leading the fight for equitable, high-quality, and culturally competent maternal and infant healthcare to end the senseless deaths of Black and Brown birthing women and infants.

Maternal mortality is the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of a pregnancy. It excludes death from accidental or incidental causes. Infant mortality is the death of an infant between one day and one year of age. Since 2019, statistical data shows a downward trend in overall maternal mortality rates (MMR) and infant mortality rates (IMR). Unfortunately, this single data point does not reflect maternal and infant mortality in communities of color. An in-depth look at the data reveals stark and persistent racial gaps in maternal and infant mortality rates among Black and Brown mothers and infants. For persons of color, the odds of surviving a birth or celebrating an infant’s first birthday are dismal.

The death of Black and Brown mothers and infants is a tragedy for families, communities, and the nation. Maternal deaths during pregnancy, childbirth, or the postpartum period indicate the quality of care provided by a nation’s healthcare systems. Infant deaths are an important marker of the overall health of a nation as they are a measure of child survival and reflect the social, economic, and environmental conditions in which children and others in society live. Researchers and policymakers use IMR and MMR data to draw conclusions and to inform policy recommendations.

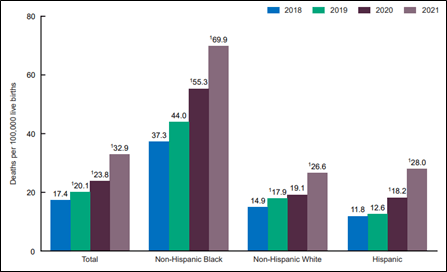

In 2021, the MMR for Black women was 69.9 deaths per 100,00 live births, two to three times the rate of White women (26.6). In 2020, the IMR was over two times higher for infants born to Black women than infants born to White women, 10.6 versus 4.4 per 1,000, respectively (Figure 1). Infants born to Indigenous women had a lower IMR in the same year; however, the rates were unacceptably high. In 2020, the IMR for White women was 4.4 deaths per 1,000 live births. In comparison, 7.7 per 1,000 American Indian/Alaskan Native infants died, and 7.2 per 1,000 Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander infants died (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Maternal mortality rates, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2018-2021

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Systems, Mortality.

Statistically significant increase from previous year (p < 0.05)

NOTE: Race groups are single race.

Figure 2. Infant mortality rates by race/ethnicity: United States, 2020

SOURCE: Infant mortality in the United States, 2020: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 71 no 5. Health Statistics. 2022. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:120700.

NOTE: Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race but are categorized as Hispanic for this analysis; other groups are non-Hispanic. AIAN refers to American Indian or Alaska Native. NHOPI refers to Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

In 2020, the top five leading causes of death of Black infants were low birthweight, congenital malformations, SIDS, accidents, and maternal complications, respectively. Comparatively, Black infant death rates significantly exceeded White infant death rates in each of the top five categories (Figure 3).

Figure 3. IMR per 100,000 live births by cause, race/ethnicity, U.S., 2020 Source: CDC 2022. Infant Mortality Statistics from the 2020 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set. National Vital Statistics Reports.

Maternal and infant deaths occur; however, the death of Black and Brown mothers and babies is unacceptable. Systemic and structural racism are persistent factors in the racial gaps seen in maternal and infant mortality in the U.S. Throughout U.S. history, and presently, racism provides privilege to some and oppression to others. In the healthcare system, racism is often an invisible and impenetrable obstacle for minority groups and marginalized populations. Even when controlling for specific underlying social and economic factors, such as education and income, racism and discrimination drive disparities in maternal and infant health.

Prolonged stress caused by historical and systemic racism strongly correlates with adverse health outcomes regardless of social status and income. Internalized, personally mediated, and institutionalized racism adversely affects the health outcomes of Black and Brown mothers and, in turn, Black and Brown babies. Anuoluwapo T Akinsanya, MD, board-certified in obstetrics and gynecology and licensed in Virginia, affirmed the impact of systemic racism on health outcomes in a recent interview. She said that as a Black practitioner, she can hear patients breathe a sigh of relief when she enters a room and patients see a healthcare provider who looks like them. Minority healthcare providers bring a sense of peace, trust, and a level of caring that is critical for marginalized populations who are often invisible in the U.S. healthcare system because of racial bias. Dr. Akinsanya supports the integration of trained doulas before, during, and after birthing as an essential component of the maternal and infant care continuum to improve health outcomes for Black and Brown mothers and babies.

For minority populations, before birth and during pregnancy, stress-related racism has major implications. Elevated stress leads to increased cortisol levels that cause stunted growth and disrupt the body’s organ systems, including the immune, vascular, metabolic, and endocrine systems. Self-reported experiences of racism are associated with adverse birth outcomes, including low birthweight and preterm delivery, as high as three-fold among Black people. Similarly, American Indians are victims of historic and persistent systemic racism. Racism accounts for a 2.9 times higher rate of late or no prenatal care among American Indian mothers than white mothers. While correlation does not prove causation, the pattern of disparities in IMR for specific populations highlights the importance of considering racism when examining the root causes of high IMR and proposing policies and recommendations to reduce disparities in infant mortality.

Internationally, the March of Dimes is a leading non-profit organization addressing maternal and infant health. The organization’s multi-pronged approach to addressing the maternal and infant health crisis involves research, public policy, advocacy, programs, and education to increase health equity and improve health outcomes for mothers, babies, and families. Policy priorities for 2023-2024 include advocacy at federal, state, and local levels to eradicate health inequities, reduce prematurity, and prevent maternal mortality. The March of Dimes priorities include:

Access to Quality Healthcare

Medicaid postpartum expansion to 12 months in all states

Medicaid and private insurance coverage for doula care

Access to telehealth for pregnant women, especially in maternity care deserts

Opposing harmful Medicaid policies and proposals that create coverage barriers

Support Healthy Women and Babies

Implicit bias training for healthcare providers before, during, and after pregnancy

Policies that provide access to mental healthcare and substance abuse programs

Workplace policies, including parental and family leave and pregnancy accommodation

Research and Surveillance

Legislation to standardize maternal and child health best practices

Federal and state legislation to protect and improve newborn screening

Promotion of key maternal and child health priorities, including health disparities

For 100 years, Black and Brown mothers and babies have died due to structural and systemic racism. Another year is too long for another maternal and infant report card to highlight the abysmal mortality rates for mothers and infants. Activism is a catalyst for change. In U.S. history, activism led to women’s right to vote, Black voting rights, and child labor law protections. Activism can change the maternal and infant mortality crisis. Learn more, donate, or join the fight to support efforts to improve the health outcomes and well-being of every mother and baby in the U.S.

Learning Resources

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Public Health on Call: 3-Part Podcast Series

Part 1: Public Health in the Field: What is the Black Maternal Health Crisis and How Can it Be Solved? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4qXx0Aio8_0

Part 2: Public Health in the Field: How Policy Can Help Solve the Black Maternal Health Crisis? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MnuKMRPKXgo

Part 3: Public Health in the Field: The Grassroots Revolution in Maternal Health

U.S. Maternal Vulnerability Index

Explore this open-source tool to identify maternal vulnerability in your state.

March of Dimes

Search for programs, toolkits, federal and state advocacy, research, reports, and more.

https://www.marchofdimes.org/

HRSA Maternal & Child Health

Learn about Maternal Child Health Month to raise awareness, find funding, resources, and more.

https://mchb.hrsa.gov/

CDC

Find tools and resources, information about national programs and campaigns, and more.

https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/index.html

References

Business Group on Health. (2022). The maternal and infant mortality crisis. https://www.businessgrouphealth.org/en/resources/maternal-and-infant-mortality-crisis

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Infant mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm

Declercq, E. & Zephyrin, L. (2020). Maternal mortality in the United States: A primer. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-brief-report/2020/dec/maternal-mortality-united-states-primer#:~:text=Systematic%2C%20comprehensive%20collection%20of%20data,deaths%20per%20100%2C000%20live%20births

Gonzalez, R. & Gilleskie, D. 2017) Infant mortality rate as a measure of a country’s health: A robust method to improve reliability and comparability. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6681443/#:~:text=Researchers%20and%20policy%2Dmakers%20often,indicator%20of%20a%20country’s%20health

Gunja, M., Gumas, E., & Williams, II, R. (2022). The U.S, maternal mortality crisis continues to worsen: An international comparison. Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/us-maternal-mortality-crisis-continues-worsen-international-comparison#:~:text=New%20international%20data%20show%20the,most%20other%20high%2Dincome%20countries

Hill, L., Artiga, S., & Ranji, U. (2022). Racial disparities in maternal and infant health: Current status and efforts to address them. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/

Hoyert, D. (2023). Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2021/maternal-mortality-rates-2021.pdf

Jang, C. & Lee, H. (2022). A review of racial disparities in infant mortality in the U.S. Children 9 (2). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8870826/

Macrotrends. (2023). U.S. Infant Mortality Rate 1950-2023. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/USA/united-states/infant-mortality-rate#:~:text=The%20current%20infant%20mortality%20rate,a%201.19%25%20decline%20from%202021

March of Dimes. (2022). 2023-2024 policy priorities. https://marchofdimes.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/2023-24%20Policy%20Priorities.pdf

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Infant mortality rates. https://data.oecd.org/healthstat/infant-mortality-rates.htm

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. (2023). Infant mortality and African Americans. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=23#:~:text=Non%2DHispanic%20blacks%2FAfrican%20Americans,to%20non%2DHispanic%20white%20infants

Author:

Kelva Edmunds-Waller, DNP, RN, CCM, has over 40 years of nursing experience, including over 20 years in leadership roles. She has clinical experience in acute care, home health, infusion therapy, public health, managed care and long-term acute care. Kelva earned a DNP degree at Loyola University New Orleans and an MSN and BSN at Virginia Commonwealth University. She serves as president of the Central Virginia Chapter of CMSA and is a member of the CMSA Editorial Board.

Contributing Author:

Nicole M. Meredith, BSN, RN, CNOR, CSSM, has over 30 years of experience in nursing practice. She has expertise in the field of perioperative care, including pre-, post-, and intra-surgical intervention. She currently practices as a case manager for complex primary care patients and families in primary care. Nicole is also a certified massage therapist.

The post Social and Political Activism Is One Solution to Prevent Avoidable Deaths of Black and Brown Babies in the United States appeared first on Case Management Society of America.

Source: New feed